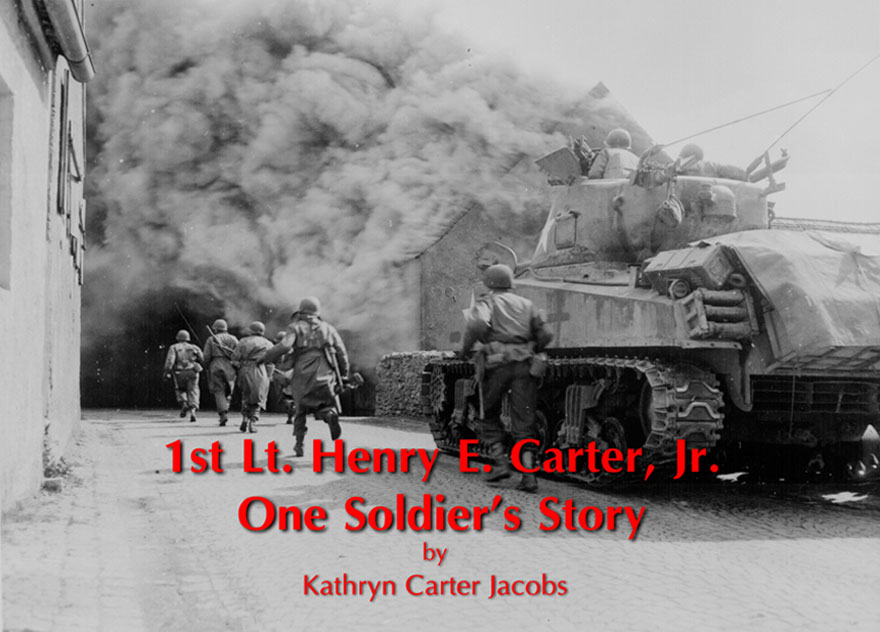

PrologueIn early 2018 I was going through a long-forgotten box of old papers, most of them Carter family records. I discovered some of my father's old US Army records, issued in the mid 1940s on yellowed, carbon copies of War Department memos. In reading these papers I noted that he had been awarded a Purple Heart and several other typical medals, of which we were aware. On two of the War Department memos it stated that my Dad was entitled to wear the D.S.C. A few weeks later my husband and I took this memo to church and showed it to our friend, Col. Guy K. Troy, Retired, US Army. Col. Troy said, “Oh my gosh, Kathi's father received the Distinguished Service Cross!”

First of all, the colonel explained to us that the D.S.C. is the second highest military award that can be given to a member of the United States Army, for extreme gallantry and risk of life in actual combat with an armed enemy force. This extraordinary heroism not justifying the Congressional Medal of Honor must have been so notable and have involved risk of life so extraordinary as to set the individual apart from his or her comrades (source: US Department of Defense.)

Secondly, my father never mentioned having earned the Distinguished Service Cross. This could be due to the fact that he was in a coma for weeks after his injuries and then hospitalized for approximately 16 months in various hospitals, recovering from his extensive wounds and five subsequent operations. Or, it may also be that Daddy was simply too modest to tell anyone.

Col. Troy urged me to contact the National Personnel Records Center for assistance which I did, to no avail. I received the standard, "On July 12, 1973, a disastrous fire at the National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) destroyed approximately 16-18 million Official Military Personnel Files (OMPF)."

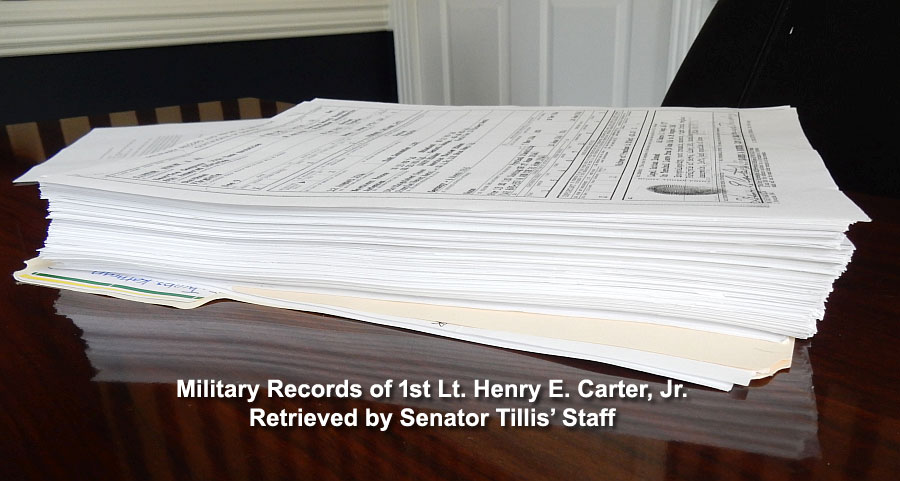

With Col. Troy's urging, I then wrote letters to our U.S. Senators and U.S. Congressmen and, with the assistance of Sen. Thom Tillis' Staff, in late April I received word that my father's D.S.C. Medal was ready for me to collect at the Senator's High Point office.

When my husband and I went to High Point I was thrilled to see and receive, on my father's behalf, not only the D.S.C but also a two inch stack of US Army military records concerning Lt. Carter's service during World War II.

The following pages of this story and the detailed history of my father's military experiences would not have been possible to write without these records and the information I found in the 8th Armored Division Association's detailed website (http://www.8th-armored.org/).

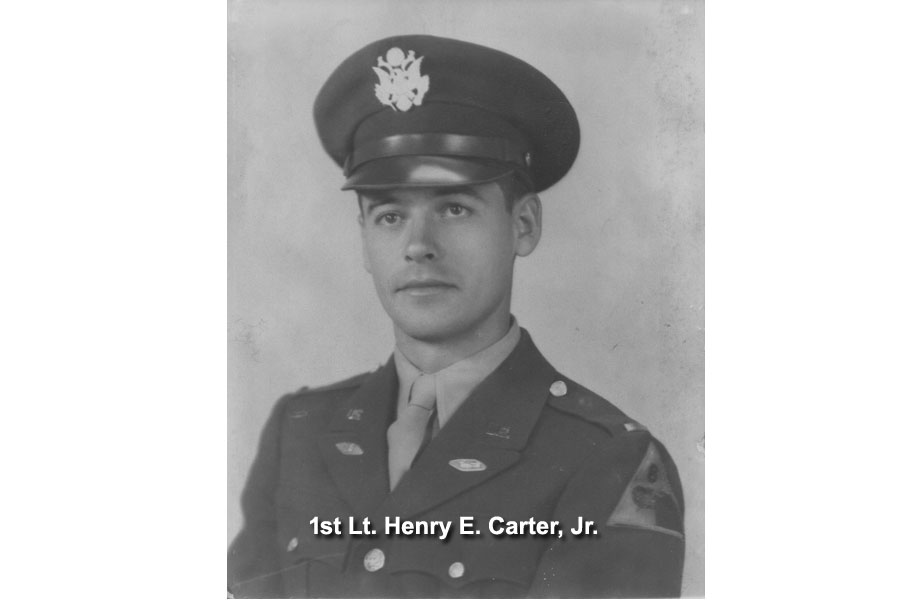

And lastly, but very importantly, it was with gratitude and humility that we attended the Memorial Day 2018 program at Highfalls Elementary School in Bennett, North Carolina. The guest speaker for the ceremony was Col. Guy Troy, US Army, Ret., who delivered an inspiring message to 250 attentive youngsters. At the end of his talk he gave these young people a brief history of the medals of valor awarded by the United States Army and then presented, posthumously, the Distinguished Service Cross to my father, 1st. Lt. Henry Eugene Carter, Jr.

My father, Henry Eugene Carter, Jr., was born on December 23, 1922 in Chatham, Virginia in Pittsylvania County. He was the first child and the only son of Henry Eugene Carter, Sr. and Martha Sue Overton Carter and was born on his mother's 26th birthday just after their first wedding anniversary. At that time his parents were living in a small white frame house on the northern edge of Chatham on Hurt Street, just beyond the intersection of Main Street and Military Drive. I do not know the year when my grandparents moved to the Woodlawn community on the southern edge of Chatham but do know they were living there by the summer of 1930 (source, 1930 Fed. Census.)

All of the families in Woodlawn (the Overbeys, the Yeattses, the Vicellios, the Prices and the Smiths) knew my father as a very young boy. In later years Mrs. Ernest (Hazel) Overbey and Mrs. Coleman (Ruth) Yeatts, Sr. shared stories of how polite and respectful he was to everyone. Miss Theo and Miss Janie Smith, unmarried sisters who taught in Alexandria, Virginia before retiring to Chatham, often talked about Daddy carrying his sister, LaRue's, books to school. By all accounts Daddy was a good brother to his little sister, who had polio as a child.

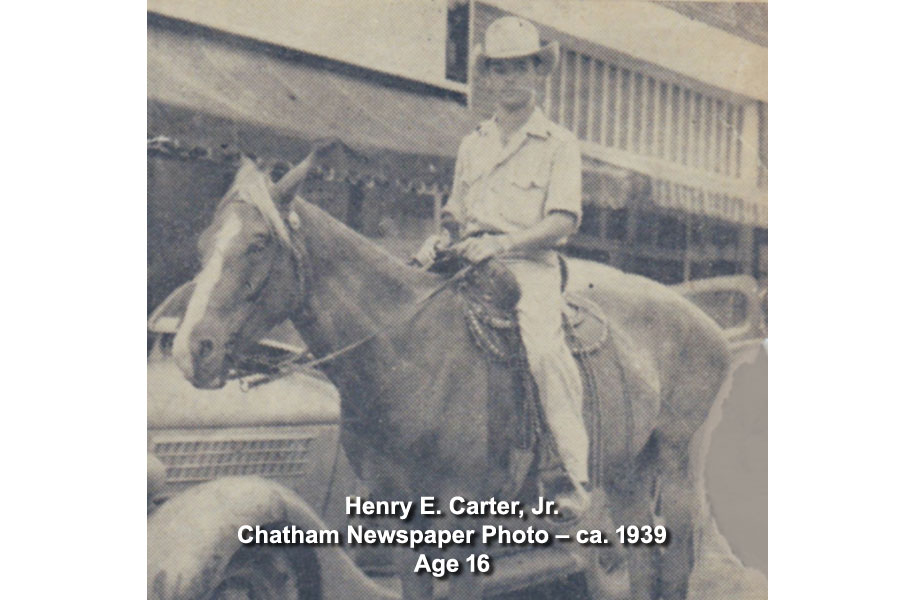

After elementary school Daddy attended Pittsylvania High School. In those days there were eleven years of public school and no kindergarten. The nuclear family in general throughout the South was strong and close-knit. Since my grandmother had been a teacher before she and Granddaddy were married, I would infer that Daddy could probably read before entering first grade. He was a healthy lad who had the usual childhood diseases but no serious illnesses or operations. In 1934 he fractured the left radius and ulna. From an early age Daddy loved horseback riding and had his own horse. He also enjoyed swimming and boxing, but his passion was always riding (“A horse, a horse, my kingdom for a horse.”) In high school he took college preparatory courses, was inducted into the National Beta Club on December 15, 1938 and was elected and served as President of his Senior Class.

As a male Carter descending from generations of men who worked, owned and loved the land of the commonwealth of Virginia it is no surprise that my father did his part to continue that tradition. While still in high school Daddy “managed large farm which worked from 8 to 12 men in caring for cattle, hogs, tobacco, hay and grain crops” (in his words from Classification Questionnaire of Reserve Officers, April 5, 1943.) The land he referenced was Cherrystone Hereford Farm, in which he had a third interest along with my grandfather. He was a proud member of the Virginia Hereford Breeder's Association, the American Dairy Sciences Association and received a Certificate of Honor in the Virginia 4-H Judging Contest 1939 for efficiency in Dairy Cattle Judging.

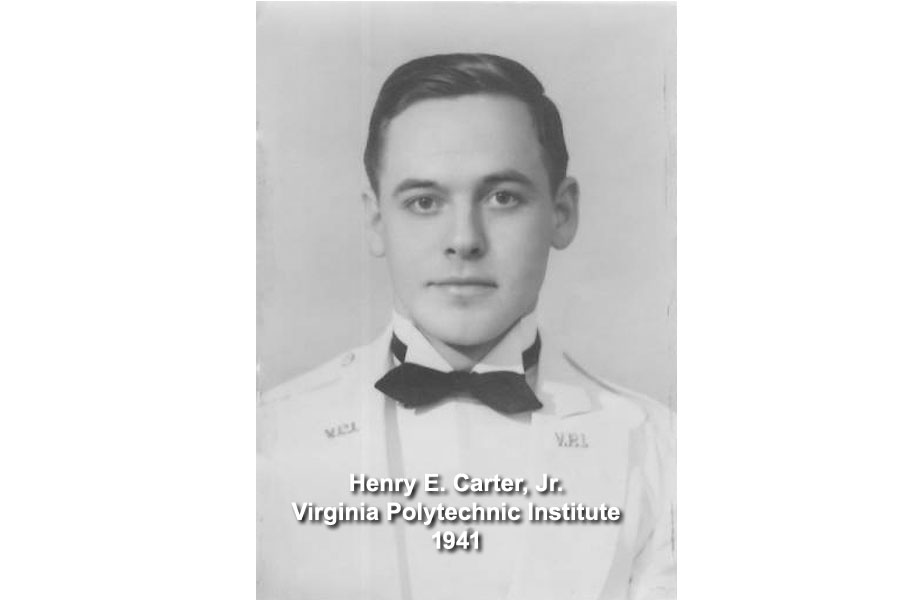

When he graduated from high school in spring 1940 there was never any question that Daddy would further his education. His plan from early on was to attend Virginia Polytechnic Institute, Blacksburg, Virginia to study animal husbandry and then go to veterinary school.

Daddy enrolled as a student at VPI on September 18, 1940. On that same day he enrolled in the Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC).

Across the Atlantic Ocean the Battle of Britain raged (July 10-October 31, 1940.) On the very day of Daddy's university enrollment London had become the direct target of the Nazis and would be bombed by the German Luftwaffe for 57 consecutive nights (September 7-November 2, 1940.)

Earlier that year Winston Spencer Churchill became Prime Minister of the United Kingdom on May 10, 1940. Had this fortuitous event not have taken place and had not the United States of America become allies with Great Britain within two years, I shutter to think what would have happened to both great countries.

While at VPI (now known as Va Tech) Daddy completed the following military studies: first year, Basic Course completed June 9, 1941; second year, Basic Course completed May 30, 1942; first year, Advanced Course completed March 19, 1943. On that date Daddy was recommended for commission in the Officers' Reserve Corps, after further training, by Col. Ralph W. Wilson, CAC, Professor of

Military Science and Tactics. According to the official Indorsement for 2nd Lt. CAC (source: W.D. AGO Form 178), Henry Eugene Carter, Jr., Company A, 3301 SU ASTU, Col. Wilson stated that my father had “excellent potential value” to the service and recommended a “first priority mobilization assignment of Troop duty – CAC.”

On April 6, 1943 Henry E. Carter, Jr. was called to Active Duty as a Private in the Coast Artillery to serve “for the Duration plus 6 months.” On the Oath & Certificate of Enlistment (source: W.D. AGO Form No. 22) the nearest relative to be notified in case of emergency was Henry E. Carter, Sr., General Delivery, Chatham, Virginia. His mother, Sue Overton Carter, was designated as his beneficiary.

From April 12, 1943 to May 28, 1943 my father was stationed at Fort Eustis, Virginia for Basic Duty (D.F.T.) at the Coast Artillery Replacement Training Center. Here both officers and enlisted soldiers were educated and trained in all modes of transportation, aviation maintenance, logistics and deployment doctrine and research. Historically, this location is of interest to the Carters due to its position along the James River. During the Colonial era this region was known as Mulberry Island and was first settled circa 1607 by English colonists. It was on nearby Turkey Island along the James River where my father's Great x 7 Grandfather, Gyles Carter, first settled in 1653.

Beginning August 28, 1943 and continuing through March 11, 1944 Daddy was back in Blacksburg at V.P.I. and enrolled in the Advanced ROTC curriculum of Chemistry, Mathematics and Physics (note: he was withdrawn for the “Convenience of the Government.”) (source: W.D. AGO Form No. 831)

On October 12, 1943 Daddy qualified for general military service in Aviation Cadet Training, Armed Forces Induction Station, Roanoke, Virginia. On November 13, 1943 the Medical Processing Unit, Nashville, Tennessee Army Air Center deemed him “physically disqualified for further flying duty because of unsatisfactory A.R.M.A. ( Adaptability Rating for Military Aviation.) Daddy never spoke of having had an interest in military aviation and so this part of his service record was a surprise to me. My dad, ever the pragmatist, was not one to waste time on regrets; rather, like other men of his generation, he moved on to a different opportunity.

On April 10, 1944 Daddy reported to The Armored School, Fort Knox, Kentucky for Officer Candidate School (OCS) and seventeen weeks of intensive training. World War II was raging in Europe and the face of combat had taken on a hitherto unforeseen menace in the form of “combat-blitzkrieg” led by German Armored Divisions. The Nazis had assembled “formations with tanks, mechanized infantry and artillery supporting one another on the battlefield” (source: History of Fort Knox, KY by Gary Kempf.) Up until this time the United States Military utilized separate training paradigms for mechanized cavalry and infantry tanks, but in 1940 top officers (among them Gen. George S. Patton) realized the urgent need to combine cavalry and infantry training.

On July 10, 1940 Fort Knox became the headquarters of the Armored Force and in that same week the 7th Cavalry Mechanized Brigade became the 1st Armored Division. This division would be led by Gen. Patton in Algeria and Tunisia. By the end of World War II the Armored Force would consist of sixteen armored divisions with more than one hundred separate tank battalions.

The Armored Force School trained armored force soldiers specifically for tank gunnery, armor tactics, communications and maintenance. In three years Fort Knox had grown in land mass to 106,861 acres and 3,820 buildings with more than 500 of them used for the Armored School. Some of these wooden buildings are still in use today.

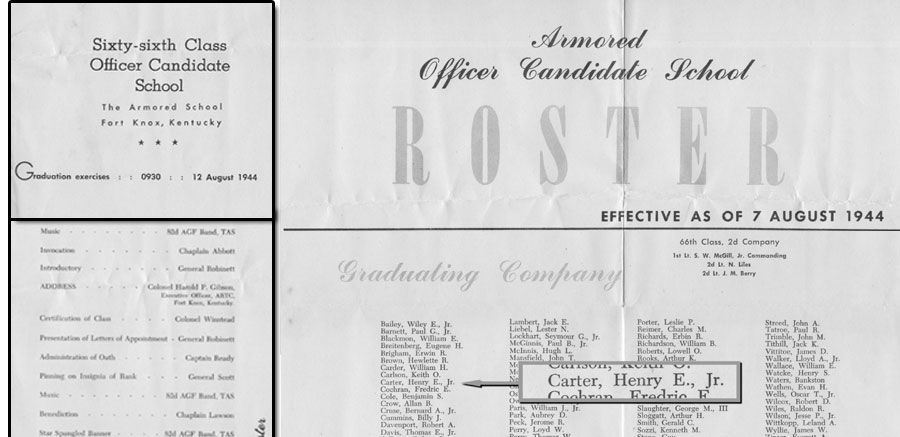

Daddy's serial number was 0556525 and his branch in the division was CA-Res, along with three other new officers: Carder, William H.; Ingrassia, Angelo J.; and Trimble, John M. (source: Restricted Extract SO 190, Par 5, HQ TAS, 10 Aug 1944.) Lt. Trimble, from Hot Springs, Virginia, returned to VPI after the war and, like my father, completed his degree majoring in Dairy Husbandry.

On June 1, 1944 Daddy was at Camp Polk serving in Company A, 36th Tank Battalion. According to the Property Issue Slip on that day he was issued the following: 1 can meat, M43; 1canteen, M43; 1 canteen cup, M43; 1 cover, canteen mtd.; 1 knife, M43; 1 spoon, M43;1 fork, M43; 1 tent, shelter half; 1 roll bed; 1 pistol belt;1 first aid pouch. These items were initial issue to the soldier but, oddly, two desired items on the slip were not issued on that day: 1 steel helmet and 1 cotton comforter (source: W.D. AGO Form 446-6 August 1943.)

While reviewing Daddy's files I looked carefully at each one because so often the story is told in the details. On the back of this form I found the handwritten names, addresses and telephone numbers of three young ladies from Baton Rouge, LA: Beverly Barton, Lucille Mayhall and Dot Mayhall. Since this original Property Issue Slip was folded into quarters, I would imagine that Daddy carried it with him and, since the back of the paper was blank, it would have been convenient to use as note paper.

At 0930 on August 12, 1944 my father graduated from the Sixty-sixth Class Officer Candidate School, the Armored School, Fort Knox, Kentucky. The graduation exercises featured an address by Col. Harold P. Gibson, Executive Officer, ARTC. The Presentation of Letters of Appointment was made by Brigadier General P. M. Robinett, Commandant. General Scott pinned on the Insignia of Rank, Chaplain Lawson gave the Benediction and the Star Spangled Banner was played by the 82nd AGF Band, TAS. On that morning exactly one hundred young soldiers were commissioned as 2nd Lieutenants in the United States Army. Of those 100 men, all of whom entered The Armored School as Corporals, 80 received orders and were assigned to duty at 8th Armored Division, Camp Polk, Louisiana.

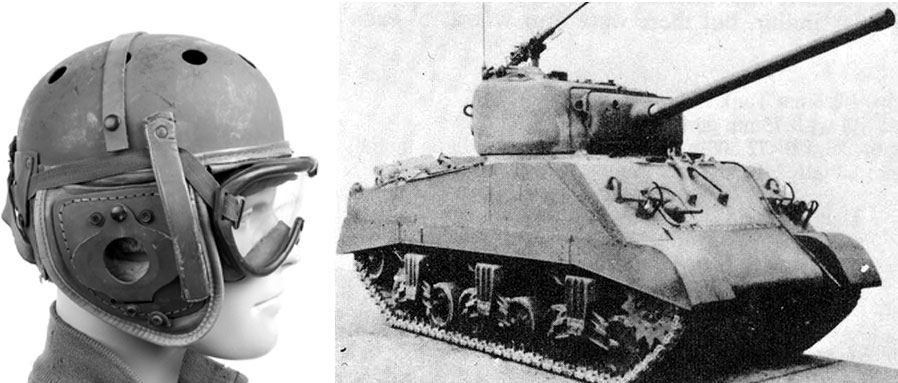

On August 23, 1944 Daddy was on active duty as Platoon Leader and Tank Commander 1203. He served in this capacity until November 20 of that year and was listed under Manner of Performance as Excellent. The responsibilities of a Tank Commander were as follows: the commander was the leader of a crew of 3-5 men (the loader, the gunner, the driver, and the radio man/bow gunner) and as such was responsible for the overall actions of the tank. He directed all tank movements, made the decisions about battlefield tactics and gave the order for engaging the enemy in battle. The commander also had to maintain communication with the squadron leader and give orders in spite of limited information being available (source: warhistoryonline.com.)

A WWII tanker's helmet was made of fiber resin and looked like a cross between a football helmet and a crash helmet. There were goggles on the front and headphones sewn into leather earflaps. (Source: Adam Makos.) Mr. Makos goes on to describe the 76mm Sherman tanks used by the American soldiers during the war:

“The thirty-three tons of tank...seemed alive. Everything vibrated;

helmets and musette bags hung from the turret, a .30-caliber machine

gun on a mount, spare tracks and wheels tied down wherever they would

fit. The tank cleared its throat with each gear change. At the heart

of its power was a 9-cylinder radial engine that had to be cranked

awake by hand if it sat overnight.” On September 4, 1944 my father was ordered to depart Camp Polk, LA on or about September 22, 1944, destination Fort Knox, KY to attend Officers' Tank Maintenance Course Class #152, with training to be completed on or about December 16, 1944 (AG 352, by command of Maj. Gen. Grimes.) Also by the same command a (Restricted) AG 352 memo was issued on September 15, 1944 deleting my father and adding Lt. Jerome R. Peck (FA.) On September 20, 1944 Daddy was assigned to CA, 36th Tank Battalion (HQ 8th Armored Division Special Order 236.)

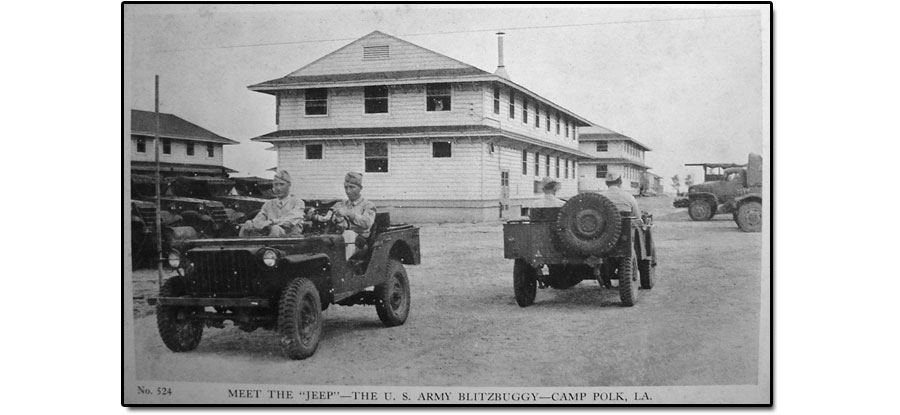

Camp Polk was built in 1941 in Vernon Parish 10 miles east of Leesville, Louisiana. Thousands of wooden barracks were quickly built to house US Army soldiers being trained for battle in the

European Theater of Operations (ETO), North Africa and the Pacific. There was an urgent need for modernization and large-scale training to test “a fast-growing, inexperienced force.” Louisiana Maneuvers were created to meet this need. In just two months' time in its first year of operation Camp Polk and the Louisiana Maneuvers trained half a million soldiers in 19 Army Divisions over a land mass of 3,400 square miles (source: matchpro.org/archives.)

For the first time in American military history it became possible to conduct massive outdoor tactical exercises. Open-field maneuvers provided armies, their commanders and all soldiers the very real experience of participating in offensive and defensive warfare (nationalWW2museum.org/war/articles.) At Camp Polk armored divisions of American soldiers were getting the necessary training in both mass and mobility covering long distances in combat in huge multi-mechanized units. These men were learning how to defeat Blitzkrieg tactics and how to withstand and survive German tank attacks in narrow areas.

In October 1944 the 8th Armored soldiers knew their Camp Polk days were soon to be over. Equipment was packed and crated. An official “alert for movement” to the Port of Embarkation (P.O.E.) was issued. Invoices verified that new equipment was being shipped to Elmira, New York. The men were advised to make wills and put their personal affairs in order. Soon the official countdown began.

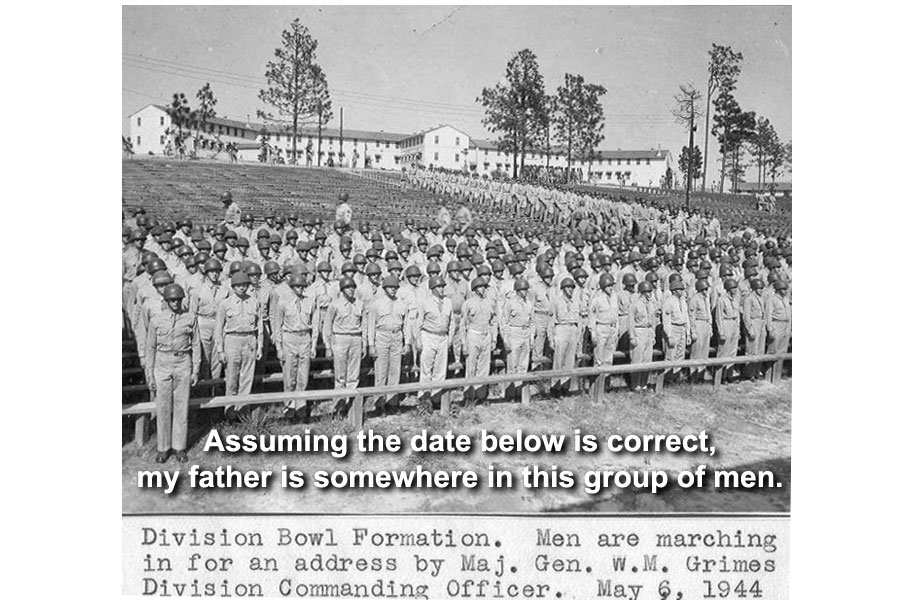

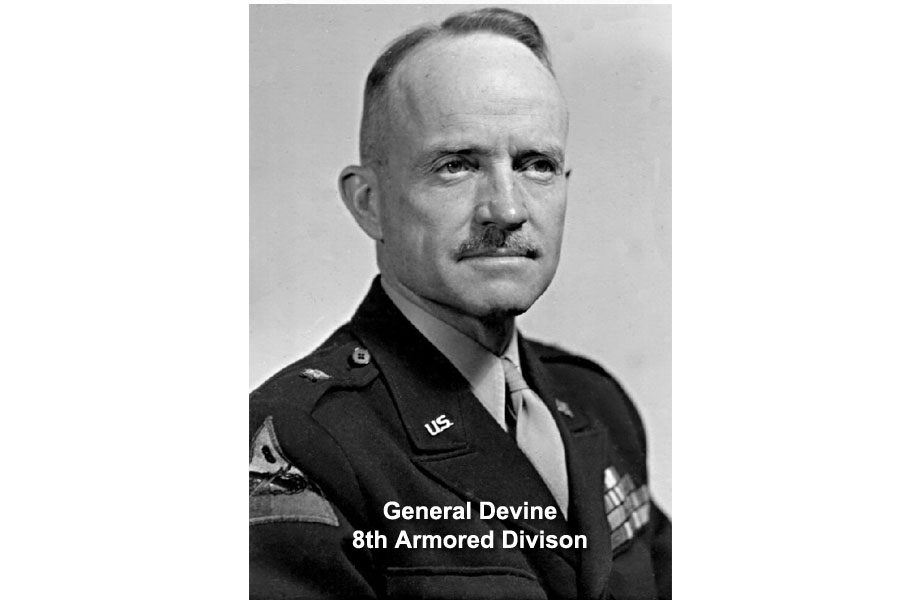

On October 18 Brig. General John M. Devine addressed the entire 8th Division in the Division Bowl. From that day through October 26 train commanders were designated and loading plans were established.

All the men in the Division felt the excitement and anticipation. On October 27 they boarded troop trains to Camp Kilmer, New Jersey (8th Armored Division - 36th Tank Battalion.) The P. O. E. was Top Secret and troop movement out of Camp Polk was unannounced. Soldiers understood this and never uttered the words Camp Kilmer until their arrival. No communication with anyone not on the train was allowed and the men kept themselves to themselves. For three days and four nights the troop trains traveled through Chicago, Detroit, across Canada and through Buffalo. The men played cards and stared out the windows.

The Thundering Herd, as the 8th Armored Division was known, arrived at Camp Kilmer on October 30,1944. The men were to be there for a total of nine days, the first three days being devoted to the issue of equipment and physical exams. Camp Kilmer first opened in 1942 and served as a major transportation hub for American servicemen on their way to or returning from the E.T.O. More than 20 divisions, including the 8th Armored, and over 1.3 million soldiers matriculated here before their deployment to Europe. The camp remained an active staging location until the end of the war in 1945.

Between November 2 and November 6 the Herders were issued 12-hour passes for a quick visit to NYC or to their homes if they lived nearby. On November 6, 1944 a final retreat ceremony was held at Camp Kilmer. The men were dressed in full uniform: steel helmet, rifle, full field hump with overcoat. Many battalions of the Thundering Herd marched the mile to the trains and stood in formation along the road as Retreat was sounded. The one hour's train trip was followed by a ride on the Staten Island ferry to the debarkation pier. The band played and the Red Cross served coffee and doughnuts (source: personal story of T/Sgt Fredrick W. Slater, Company D, 36th Tank Battalion.) Roll call (“Carter” with a reply of “Henry E., Jr.”) was taken as the men boarded the troop ships that evening of November 6. Heavily burdened with battle gear and moving purposefully into cramped quarters the 8th Armored Division felt itself in good hands under the command of Gen. Devine.

Four ships carried these servicemen to England that night: HMT Samaria (a royal mail ship built in 1921;) USAT George W. Goethals; USAT Marine Devil; and SS St. Cecilia (source: In Tornado's Wake, Capt. Charles Leach, Company A, 7th AIB.) I do not know on which of these ships my father sailed because passenger lists were deliberately destroyed in 1951 by the Department of the Army (source: WW2troopships.com/crossings/1944.) It is believed, however, that most of the 8th Armored soldiers were transported on the Samaria which regularly accommodated as many as 4,440 troop officers and enlisted men. This was slightly more than double the number of passengers when the Cunard White Star Line sailed commercially prior to wartime.

In stark contrast to my father's New York to Southampton transatlantic crossing – 65 years later, to the very week! - my husband and I were on the same journey in reverse direction – and on a Cunard ship as well - the Queen Mary 2. Our ships might have passed each other on the North Atlantic on the same route, exactly 65 years apart. The North Atlantic in mid-November can be treacherous, when we crossed it November 2009 in a ship specifically built to cross the North Atlantic we encountered gale-force seas and waves so high that they broke over the top deck of QM2, the largest ocean liner in the world. The ship was tossed around so violently that hundreds of crew members and passengers were confined to staterooms and quarters due to seasickness.

By normal standards the size of a military division was 10,000-20,000 men. In World War II that number swelled to as many as 30,000 men. Since the majority of the Thundering Herd 8th Armored Division sailed out of the Brooklyn Terminal bound for Southampton on the same night, they surely would have traveled in a convoy. Troop transports would usually have a strong naval escort, including destroyers. Normally a convoy had a rectangular formation but weather conditions could affect that positioning. Convoys across the Atlantic usually took a circuitous and evasive route that would cover between 3000 and 5000 miles; and, when traveling in a convoy, your speed is determined by the slowest ship (source: militaryhistoryonline.com/wwii/.)

The following excerpts from men on those ships state in their own words the conditions of that overseas crossing.

“The men...turned their eyes to the New York skyline

as their ships eased out...and headed to sea. As the

ships closed in on the rendezvous area and the convoy

was formed, a combined British-American naval team

began to escort the Division across the Atlantic Ocean.

In addition to those activities the men read, watched movies, slept and practiced with their life jackets known affectionately as “Mae West.” It was a Saturday morning when Armistice Day was observed at 1100 hours on board each ship. In formation soldiers observed a moment of silent prayer as they faced East on that November 11 to remember those men who had made the ultimate sacrifice in “the war to end all wars.”

One week later on November 18 the ships in the convoy dropped anchor just outside the harbor of Southampton. Once again the Red Cross was there in the big shed to provide coffee and doughnuts. On November 19 debarkation, a lengthy process complicated by the weight and bulk of heavy battle gear, took place. It was dark as the men made the transition from sea legs to walking again on land. Trains were boarded heading northward. Here the Herders had their first look at the dreadful results of the German bombs.

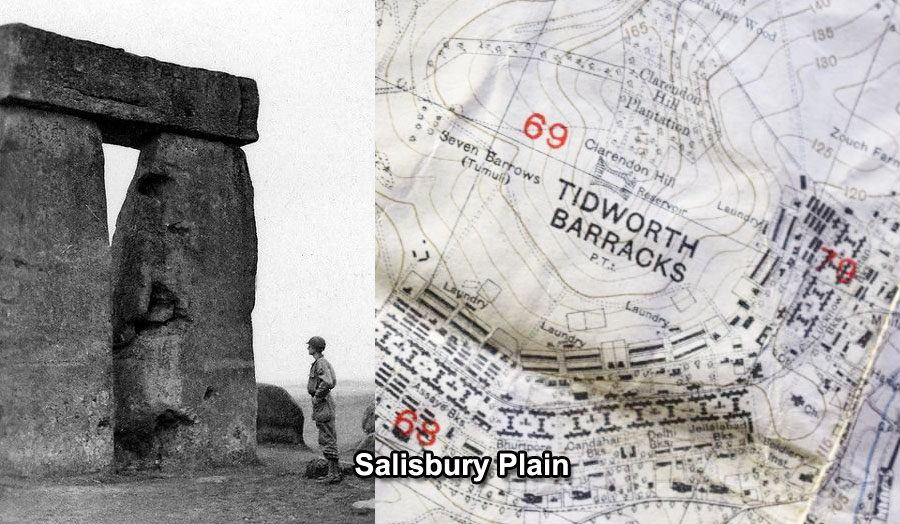

The trains took the men on a two-hour ride through southern England to the Salisbury Plain. Their destination was Tidworth Barracks where the men found their bunks and “hit the hay” - literally, as they were now sleeping on straw mattresses. Tidworth was first designed by Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany for Queen Victoria's troops. The majority of the 8th Armored was housed in barracks sporting exotic Indian names. Other battalions were assigned to crude 8-man tents but given the ingenuity of soldiers these tents were soon improved with floors, siding and doors for exit and entry. These barracks and tents were to be their base for the next six weeks.

Initially the rain and relentless mud of their midwinter arrival was miserable, but after a short while other matters occupied their thoughts. Training and the issuing and processing of equipment took the lion's share of a soldier's time. These men were aware that preparations were being made for an imminent move across the English Channel.

Nonetheless nearly every soldier of the 36th Tank Battalion was issued a 2-day pass to London. Here they had their first look at the results of systematic bombing during the Battle of Britain. Four years on the Londoners were going about their everyday affairs with resolve and purpose. My father never spoke about London but did say that he was very impressed with Stonehenge on the Salisbury Plain.

In a very real sense England was a step back in time and place. In the countryside the thatched-roof cottages and winding lanes, the open fields laid out in neat squares, the country folk calmly looking after one another and carrying on in the midst of very real longterm hardship – surely all of this made it abundantly clear to these young men the difference in resources of the United States and Great Britain.

During this time in Tidworth the men also had the opportunity to meet and socialize with English girls in Andover, Amesbury and Salisbury and both civilian girls and ATS girls from Bulford Barracks enjoyed the dances given by various companies.

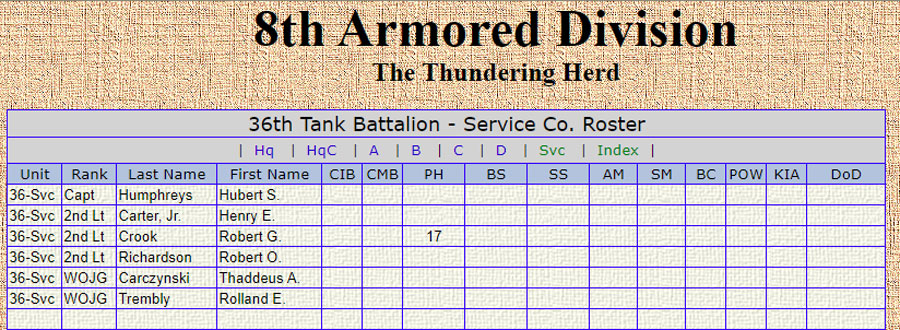

My father had been promoted to 1st Lt., CAC, on November 21, 1944 and was appointed Battalion Transportation Officer #0600, Service Company, 36th Tank Battalion, In that capacity his responsibilities were to procure and maintain necessary supplies for the battalion and to keep the organization functioning (W.D. AGO Form 100.)

On December 11 and 12 of 1944 the now famous “Patton Prayer” was distributed to the men of the Third Army:

In response to the prayer, the weather lifted on 20 December.

Thanksgiving and Christmas Days were workdays for the men, but on both occasions they enjoyed specially prepared hot meals with turkey and dressing. This in itself was remarkable given the stringent rationing of food in England. Having seen the want and the deprivation, the soldiers shared their bounty with orphaned children from Salisbury.

By the winter of 1944 Nazi Germany faced a grim situation. Soviet forces were closing in from the east as were British and American forces from the west. Hitler's intention to launch a surprise attack in the west was foiled by key roads being blocked and Gen. Eisenhower's order to send in massive reinforcements.

Everyone was aware they were in a holding pattern while in Tidworth and so the departure for Southampton on January 2, 1945 came as no surprise. By 2200 hours on January 3 the 8th Armored Division has boarded LSTs and was crossing the English Channel headed for France.

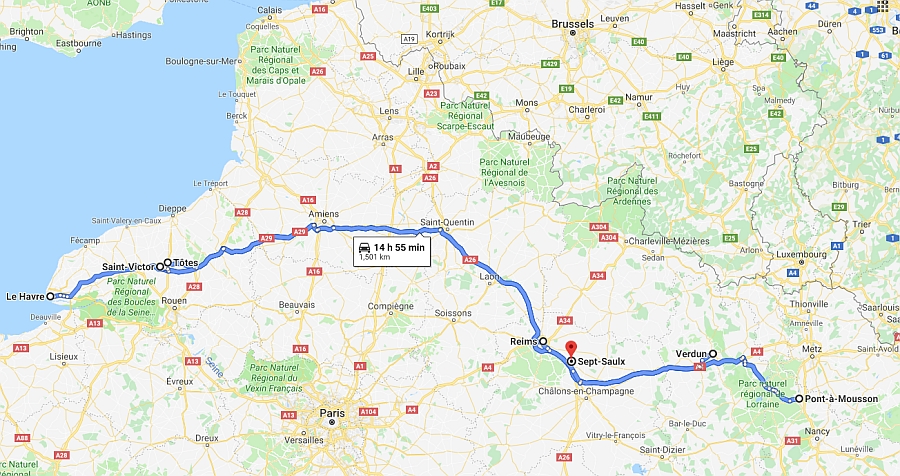

On January 5, 1945 landings took place at both Rouen and Le Havre and troops assembled in upper Normandy at

Bacqueville, France to make camp. After crossing the Channel the troops moved through the Ardennes: Totes, St. Victor, Gournay, Beavais, Breales, Soissons, Rheims, Suippe, Verdun, Mars la Tour, Pagny-a-Mosille and Pont-a- Mousson to St.-Jure. Between January 7 and January 10 the Division made the

175 mile trip to Rheims and set up headquarters in Sept-Saulx. (source: 8th Armored Division, Division History, January 1945.)

On January 11, 1945 the Division was officially assigned to join operations with the Third Army, under the command of General George S. Patton. My Dad did not talk much about the war but, on more than one occasion, he did tell me that for a brief time he had served as the youngest officer on Gen. Patton's staff. I have no documentation to verify his statement but think there was some small, brief connection between them during this chaotic troop movement. My father had great respect for General Patton.

Years later I came home one weekend from Salem College and told my parents I was dating Gen. Patton's grandson. My Dad was so impressed that he and my mother drove me down to Ft. Bragg over the Christmas holidays to personally meet the young man. Henry Carter, Jr. was not easily dazzled but, in that case, I believe he was!

On January 12, 1945 the Division raced 105 miles across France reaching Pont-a-Mouson the following day. On January 13 the Division took on TORNADO as its code name and joined up with the 148th Signal Company. During this incredible trip a blinding snowstorm blanketed the country, roads were rutted and covered with snow and ice, and tanks and half tracks (wheels at front, caterpillar tracks in back) were sliding into ditches. “It was said that you could trace the march of the tanks of the 8th across France by checking the skinned trees along the roadside, which in many cases kept the vehicles from falling off the road.” (source: In Tornado's Wake, Capt. Charles R. Leach)

From January 12 to February 2, 1945 the 36th Tank Battalion quartered at St.-Jure, France. During this time the men used abandoned forts along the French Maginot Line for combat training by Third Army. Temperatures hovered around zero degrees so trenchfoot and frostbite were real dangers.

The Ardennes in North France became known in World War II as the Battle of the Bulge (December 16, 1944-January 25, 1945.) It was the last major German offensive campaign on the Western Front during the war. When the Nazi resources were depleted and collapsed the Allies forces were able to break the Siegfried Line and achieve victory.

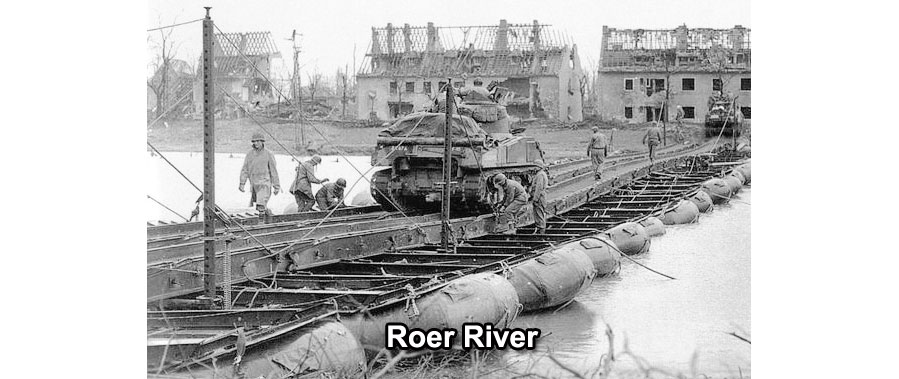

From February 3 to February 20, 1945 the Herders were stationed in Liege, Belgium and Margraten, Holland. (Here a battlefield cemetery was first established in November 1944.) For nearly two months the frozen and muddy ground made tank movement difficult and these conditions combined with flooding made crossing the Roer River impossible. During this time the 36th Tank Battalion was attached to Combat Command B (CCB) from February 7 to February 18 and was still on the Top Secret list of 9th Armored Division. On February 21 their job was to occupy ground between St. Odlienberg and Posterholt, Germany. My father was assigned to Task Force Van Houten (Major John H. Van Houten, Commanding Officer, 36th Tank Battalion) and this task force was to occupy the northern section of the line. From February 21 through February 23 the CCB received information from the British about mine fields and obstacles to tanks. The men of the 8th during those few days and nights admired the ingenuity of their compatriots who had dug out foxholes and caves for shelter and safety. On February 23 Operation Grenade began on the west bank of the Roer River with the orders to proceed north to the city of Roermond.

On February 27 the men of XVI Corps crossed the Roer and thus opened a way for the 9th Armored Division to get to the Rhine River. That same evening CCB reached the Hilfarth bridge and prepared to mount an attack on Arsbeck the following day. On February 28 the town was cleared by the middle of the afternoon and General Devine issued orders for Combat Command B to halt movement. Boundaries were being redrawn while separate combat divisions were receiving ever-fluctuating troop movement orders throughout the region. On March 3 Task Force Van Houten picked up the offensive to relieve Combat Command A and head for Alderkerk. German troops were known to be in this town so it was to be surrounded before the Americans entered the town. A good many of the military directives of these few days boiled down to “hurry up and wait.”

“At 2300 hours on March 4 Combat Command B was attached to the 35th Infantry Division (source: XVI Corps Letter of Instruction 27) and was ordered to continue toward Lintfort and Rheinberg to secure the bridge at Wesel. These combined forces were to close a gap at Wesel, the point where Germans were fleeing across the Rhine.

CCB was instructed to proceed from Alderkerk “northeast to the tree line on the ridge overlookng Lintfort” and be ready to attack the town at 0800 hours on March 5.” (source: In Tornado's Wake, Capt. Charles R. Leach.)

When these orders were given it was believed that Rheinberg itself would be an easy capture for the Allies. German troop numbers in the town were thought to be low and in a demoralized state. Intelligence reports stated light opposition so no air reconnaissance was provided beyond Lintfort.

In hard fact Rheinberg was “some of the toughest, bloodiest fighting in which the 8th ever engaged.” (source: In Tornado's Wake, Capt. Charles R. Leach.)

Lintfort was captured before sunset the next day. A radio message received on March 5 at 1500 hours was not properly encoded and by this time the trains (convoys of trucks) were loaded with supplies for the 36th Tank Battalion and were ready to move to resupply troops at their location between Lintfort and Rheinberg. When the message was decoded the order was given to send forward six truckloads of ammunition.

The train reached Lintfort at 1900 hours on March 5. German snipers were hidden away in the houses of the town. The Herders were guarding their vehicles waiting for supplies to reach them. The Americans guarding the gasoline and the ammunition trucks were exposed to grenade attack so they strafed the Lintfort houses using 50 Cal. machine guns and 30 caliber machine guns mounted on the trucks. According to Capt. Humphreys' detailed narrative those houses went quiet in Lintfort after the strafing.

Orders were then issued to Capt. Humphreys to send two groups of trucks forward to the companies, group A and Group B. Group A was under the command of my father, Lt. Carter, and Lt. Robert O. Richardson. Their orders were to follow the road along the canal leading into Rheinberg from the western side of the town, seize the Wesel bridge and force a bridgehead on the east side of the Rhine.

Contrary to what was expected the Germans had surrounded the town of Rheinberg with 88 mm anti-tank guns with twin 44 mm anti-tank weapons near each 88 mm gun.

Information was sketchy regarding the whereabouts of Company A. This company, led by Captain Kemble “Cowboy” Tucker, was headed across the Fossa Canal road north to the canal bridge which was blown up as the tanks approached. Captain Tucker died that day.

Company A and Company D were thought to be near that location and it was unknown how many of those men were still in the area along the canal. The two lieutenants continued on past several burning tanks until they reached an impasse with a tank blocking the road one mile outside of Rheinberg.

I was not there on the evening of March 5, 1945 so I do not know what it was like for my Dad and the other brave soliders who fought in the battle of “Bloody Rheinberg.” In truth I cannot fathom the situation they faced. For this reason I am grateful to have multiple firsthand AARS (After Action Reports) given and preserved on March 16, 1945 in Venlo, Holland by the personnel of Service Company, 36th Tank Battalion.

“About 2215 hours we were ordered to form and dispatch

two seven-truck trains, to go forward to supply the Battalion

which was engaged in a fierce battle at Rheinberg.

And this AAR:"

“Lt. Richardson and Lt. Carter were with the group (Group A)

I was in. It was dark by then and must have been near 9 PM.

We moved out in perfect blackout not even using 'cat lights.'

After traveling a short distance we came to several of our

tanks still burning along the road. Everything seemed to be

burning all around us and trees and wire were hanging or

laying all over the road. We could hear the firing and saw

flashes and knew it was close. Not long after that we came

to a tank blocking the road. Lt. Carter and Lt. Richardson

went ahead with the peep leaving Cpl. Lanier and a few others

to fill in a hole so trucks could get by the tank. They had gone

just a short distance when we saw a flash. The peep had hit

a mine. Lt. Richardson came back for help but they couldn't get

to Lt. Carter who was seriously injured.

But the most detailed AAR is preserved in this verbatim testimony of Lt. Robert O. Richardson, the officer who was at my father's side the night of March 5, 1945 when he was critically wounded.

“At about 2130 hours Lt. McDonald (HQ Co Mortar Officer) was

available to guide two separate trains by different routes to the

companies.

The hours between 2300 March 5, 1945 and 1230 March 6, 1945 were dark ones for 1st Lt. Henry E. Carter, Jr. Due to mortar fire during the night the Medics were unable to retrieve men killed or wounded during the battle of Rheinberg. During those twelve or so hours my father lay under enemy fire in the bitter cold March night, critically wounded, bloody and unconscious – a blessing in his condition.

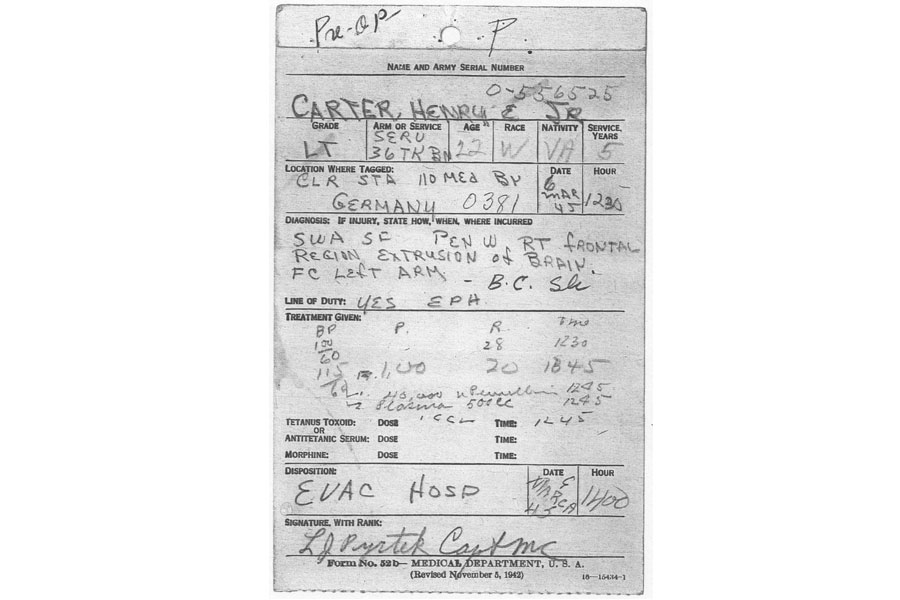

The first documentation of his whereabouts is given on Form No. 52b-Medical Department, U.S.A. (revised November 5, 1942.) This form was used by the Army to tag and identify soldiers moved from the scene of battle to hospital units. At 1230 hours March 6, 1945 Lt. Carter, Henry E. Jr., Service Company, 36th Tank Battalion, was tagged at Clearing Station Germany 0381 by the 110th Medical Battalion.

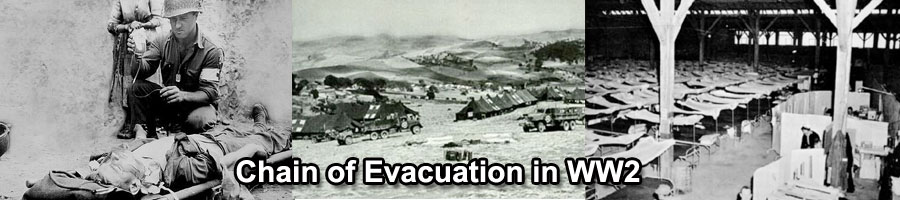

At 1400 on March 9, 1945 he was transferred to the 119th Evacuation Hospital, Germany where he remained until March 17 of that year. An evacuation hospital is defined as a mobile field hospital in a combat zone. Serious cases were sent on to fixed (general) hospitals for further care. These were large facilities where soldiers received long-term, sometimes specialized, treatment. On March 17 he was moved first to 32nd General Hospital and then to 56th General Hospital in Belgium where he remained until March 20.

On March 20, 1945 Daddy's mother received this telegram (Battle Casualty Report) from the War Department:

“The Secretary of War desires me to express

his deepest regret that your son, Lt. Henry E.

Carter, Jr. was seriously wounded in Germany

on 6 March, 1945.”

Unbeknownst to his parents, on that same day Daddy was moved to 50th Field Hospital and on March 21 to 154th General Hospital where he was treated until June 1, 1945 (source: APO 226, US Army Ward 42.)

My father's final diagnosis stated as follows:

“1. Wound, penetrating, severe, scalp, skull, dura and brain, right frontal region and frontal sinuses. WIA BC SFW incurred as a result of enemy action in Germany.

Two months later, my father was still in very serious condition in the 154th General Hospital when V-E Day was announced.

“V-E Day, announced in a SHAEF communique on 8 May 1945,

brought the war in Europe to an official end. To the men of the

Thundering Herd it was a joyous day, but one for reflection and

remembrance. Here ended a long trek that had begun more than

a year before in the Louisiana bayous. Three hundred and ten members

of the Division had given their all for their country. 2,626 had sustained

wounds, although many of these had already returned to duty.

The majority of the members of the Thundering Herd that had been

killed in action were interred in the American Military Cemetery

at Margraten, Holland. On Memorial Day General Colson headed

a delegation from the 8th Armored at services held there. Wreaths

were placed on graves of all Division members killed in action.”

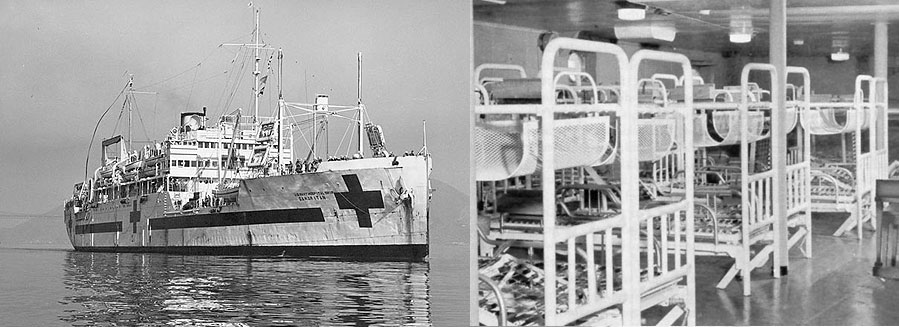

On June 1, 1945 my father was put on board a hospital ship headed across the Atlantic. Per Evacuation Order No. 160 a total of 315 wounded soldiers (23 commissioned officers and 292 enlisted men were evacuated from overseas unassigned status to the Detachment of Patients, 4137 US Army Hospital Plant. Lt. Carter arrived June 13 at Camp Shanks, New York. On June 17, 1945 my father was moved to McGuire General Hospital, Richmond, Virginia where he was treated until January 1946.

(source: Veterans Administration Insurance

Form 357, rev. Feb. 1945)

From January 17 to June 27, 1946 my father's treatment continued at Cushing General Hospital, Framingham, Massachusetts until he was granted Terminal Leave from June 30, 1946 until August 29, 1946.

Between March 7, 1945 and January 31, 1946 my father had five major surgeries: two while still in the E.T.O. overseas and the last three in general hospitals in Richmond, VA and Framingham, MA. In total he was in military hospitals from March 6, 1945 to June 30, 1946 – a total of 15 months, 3.5 weeks.

On June 25, 1946 my father appeared before the Army Retiring Board at Cushing General Hospital. He was duly sworn and then advised of his rights by the President of the Board.

The following excerpts are direct quotes of my father's testimony to the Board.

“Q. State your name, rank, serial number and organization. A. Henry E. Carter, Jr., First Lieutenant, 0-556525, Coast Artillery, formerly with the 36th Tank Battalion, 8th Armored Division, 9th Army; presently, Detachment of Patients, Cushing General Hospital, Framingham, Massachusetts. Q. Will you state the nature, duration, and cause of any disability that you believe you have? A. Insofar as I know, sir, to the best of my ability, I think I have head injuries and arm injuries. I have a tantalum plate in the right frontal region of my head, one blind eye, and partially paralyzed left arm, which were incurred on 5 March, 1945 in Rhineburg, Germany. The cause was enemy action. We were trying to cross the Rhine River just about one-half mile from the place where I was wounded. Q. Do you believe that your disability was incurred in combat with an enemy of the United States or that it resulted from an explosion of an instrumentality of war in line of duty? A. I'm positive it was. Q. Will you state the reasons for your conclusion? A. At the time I was battalion transportation officer from 36th Tank Battalion and had orders to carry ammunition and gasoline to the fighting tanks on the outskirts of Rhineburg, Germany, and during the time that I was trying to carry this ammunition and gasoline up to the fighting elements of the battalion, my vehicle ran over an enemy mine which exploded and injured myself, my driver and one other lieutenant we were with. Fortunately, the others were not wounded very seriously. Q. Do you desire to be relieved from active duty? A. Yes, sir. Q. Will you give the reasons for your answer? A. I am very anxious to continue my college education as soon as possible, and I have intentions and I desire, if relieved from active duty, to enter school on 8 July, 1946 and try to continue my education. Q. If the board finds that you are not qualified for general service, do you desire to remain on active duty in a limited service status? A. If I'm not retired, I intend to stay on active duty in a limited duty status or anything I'm called upon, I'll do my best to carry out.” And so 1st Lt. Henry E. Carter, Jr. retired from active military service with an Honorable Discharge. Almost immediately upon release from hospital he returned, as planned, to Virginia Polytechnic Institute, Blacksburg, in early July 1946. Six months later in December 1946 he was awarded his college degree in Dairy Husbandry.

My father then returned to his native home in Chatham, Virginia and re-established his life in the rural South. For the next eight months he lived with his parents and resumed his work on the Carter family farms. He traded the 76 mm Sherman tank for his horse, “Red Eagle.” He renewed his friendship with my mother, with whom he had attended high school, and this turned into a courtship. On August 30, 1947 Miss Mary Astor Motley wed Henry Eugene Carter, Jr. at 8:00 PM Saturday evening in the sanctuary of Weal Presbyterian Church. A reception followed in the Carter home in Woodlawn.

The next day the newlyweds left for a southern wedding trip. They spent the first night of their honeymoon in the O'Henry Hotel in Greensboro, North Carolina. Their final destination on this trip was Auburn, Alabama, the home of Auburn University where my father began his veterinary studies. Stories were shared with me about his life-long ambition to become a veterinarian. It was a natural fit for a young man brought up to appreciate, tend and treat animals.

Sadly, this veterinary degree was never awarded. Having vision in only the right eye, my father's opthalmic doctors informed him that close-eye work with microscopes was likely to render him totally blind. He and my mother discussed this prognosis and quickly reached the decision to return to Virginia. They left Alabama after the first semester.

Once back in Chatham life continued in the normal routine. The young men who returned from war overseas had settled into educational opportunities made available by the GI Bill, or taken jobs, and met and married sweethearts. In the late 1940s the “Baby Boom” began in earnest as young couples looked forward to building lives and families together.

In early 1950 my parents bought a three-acre farm just south of Woodlawn and Cherrystone Creek. My grandfather and father were still managing their Cherrystone Hereford Farm and knew the area well. I was born that year and began my life with Mary and Henry Carter in their new 2-story brick home. On November 6, 1952 my parents paid M.B. English and wife, Josie, the sum of $280.00 cash in hand for the property described as follows:

“Beginning at the corner of property of Henry E. Carter, Jr.,

on the East Side of Highway No. 29, thence along the right-of-way

of Highway No. 29 to stake in said highway right-of-way line

thence a new line in an Eastern direction 360' to stake, thence

South 240' to corner of Henry E. Carter, Jr. property, thence

along the line of Henry E. Carter, Jr., 360' to Highway No. 29

and containing two acres, more or less.”

Now that my father's five-acre property was complete, in addition to managing the existing family farms he could at last raise and tend livestock on his very own farm. Throughout my very happy childhood Daddy raised cattle, sheep and pigs – all of them healthy in large part due to his own original veterinary wound care ointments.

For the next forty years my father led a happy and purposeful life. During all of those four decades he was a wonderful Dad to me: showing me how and where to plant tomatoes in the garden; teaching me how to shear a sheep; giving me a pig of my own to care for; and teaching me arithmetic on the basement steps at the age of three. He drove me and my best friend, Ginger, every day to Delma Reynolds' private kindergarten and the next year began driving me each and every day to Chatham Elementary School in his old Ford pick-up truck. On many occasions he took me with him to Planters Bank in downtown Chatham and proudly introduced me to every farmer and business man in town. He and my mother took me to church every single Sunday at Watson Memorial Methodist Church on Main Street. I would sit with Daddy while Mama sang in the choir. Every Sunday evening the Carter, Jrs. would have dinner with my grandparents in Woodlawn.

My father taught me the difference between right and wrong, and when I was wrong he was quick to make me responsible for correcting my behavior. In equal measure he taught me to be kind and respectful and to do my very best to help others who needed a hand.

Daddy was an active member of the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW,) the American Legion and the Disabled American Veterans (DAV.) On Memorial Day he would proudly don his US Army uniform and sell poppies in front of the historic Chatham Courthouse. Throughout his life he was proud to have served his country and to have fought for the freedom which we enjoy today.

In April 1990 my father became sick and was diagnosed with terminal lung cancer. At his specific request he received all medical treatment at McGuire VA Hospital in Richmond, Virginia, where he had been treated upon his return stateside after being injured in World War II. For the next 1.5 years he alternated between living at home and in hospital. On October 21, 1991 he died at McGuire at age 68.

On October 25, 1991 1st Lt. Henry Eugene Carter, Jr.'s flag-draped casket was transported from the Methodist Church and laid to rest in the family plot at Hillcrest Memorial Park, Chatham, Virginia.

He was given a military funeral surrounded by family and friends and, on that clear autumn day,

Taps was played one last time for my father.

For the week of Daddy's funeral their house was filled every day with friends and neighbors who brought food, offered hospitable and dignified greetings to all who called upon my mother and in general did everything possible to ease family members at a very sad time in their lives. One particular friend of the family was most helpful in coordinating with the US Army to have Daddy's military uniform and medals and ribbons in tiptop shape for his burial.

After the service, my mother's home was still filled with close friends who had prepared a nice luncheon afterwards. Suddenly (and quite to the dismay of some) this same friend appeared at the back door with two saddled horses. He asked to see me and, after a somewhat strained reception by the ladies working in the kitchen, was able to have a brief conversation with me. This man, who had been a close friend to Daddy during his illness, always “talked the talk and walked the walk.” Never known to worry too much about tact and propriety, he sensed that I needed some closure to what had been a trying day to me. Hence, his appearance with the two horses. I immediately went upstairs and changed from my black suit and high heels into riding pants and boots.

We rode together from the house along Highway 29 past Cherrystone Creek and back to Hillcrest Cemetery. By the time we reached Daddy's newly covered grave the sun was about to set. And it was there on that hilltop with my father's friend, Harry, that I said a goodbye to my Daddy in the most fitting way I could ever imagine.

|

Copyright 2019 Kathryn Carter Jacobs - All Rights Reserved